October 2006, San Francisco. I’m writing this on my laptop at San Francisco International Airport. I got here too early and now the flight has been delayed 2 hours. Sitting here by myself with my two carry-ons-a small, nothing-special camera case that’s maybe 15 years old and a Gap $12 shoulder bag with my MacBook, black of course. I usually have an assistant, too, but that wasn’t possible for this shoot.

A MacBook running iChat sits on boxes in front of the victim, so she sees Burton, who is 2,000 miles away, and Burton can see her.

Flying tonight to Edmonton, Canada. Will shoot a laboratory and do the interviews greenscreen-Burton not coming. Will use iChat for the interviews. Who’s Burton?

Good question.

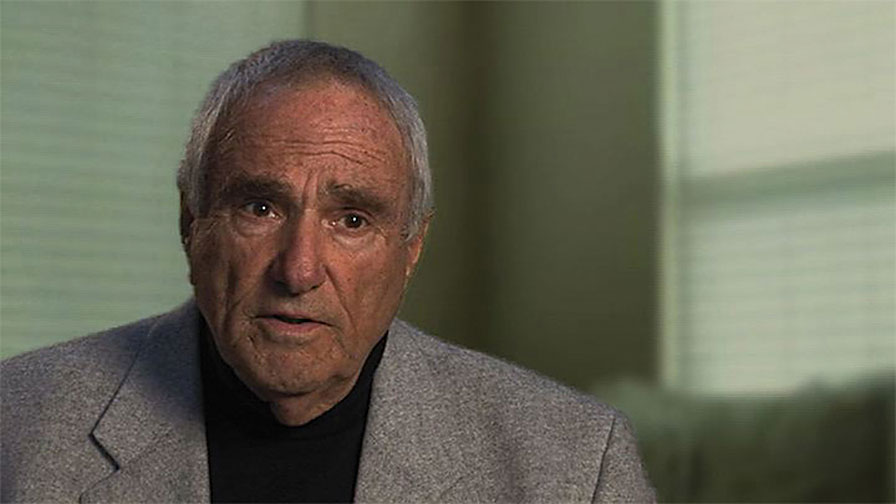

I met Burton through a neighbor who designed hotel rooms for Burton 35 years ago. After World War II, Burton Goldberg was a real estate developer who bought huge amounts of property and turned it into hotel rooms and members-only nightclubs in the Miami area. When Burton left the hotel business, he became interested in alternative medicine. With a ton of enthusiasm, but no medical qualifications, he published 18 books on alternative medicine and started the popular Alternative Medicine magazine, which he sold in 2004. At 78, he turned to producing movies.

I created a Web site for him in-it must have been mid-2003. Put a few short “Hi, I’m Burton Goldberg” Flash 7 videos on it (www.burtongoldberg.com). Then, just before Thanksgiving 2004, he phoned. “I want you to go to Germany with me tomorrow,” he said.

“Huh? Tomorrow?”

Apparently Burton had lined up “a girl” to shoot this video about conquering cancer, but she had pulled out at the last moment (the day before) because the camera he bought for her didn’t turn up. “She’s a flake–I don’t work with flakes!” explained Burton. I was cast as the last-minute replacement.

I couldn’t do “tomorrow,” but a week and a bit worked. In my suitcase I packed clothes plus three lights (a Rifa 500-watt soft light, a 12 V Dedolight, and a mini Kino Flo), a couple of lightweight tripods, my Sachtler dolly wheels, and about 35 used DV tapes–all in one case. My carry-on bag had two Micron radio mics, a Sony PD150 (hey, this was 2004) and a PDX10, some more tapes, and batteries.

On the flight to Germany, Burton told me we were making a 10-minute DVD, so I decided to shoot 16:9 using the PDX10, which does–or did–a much better widescreen than my aging PD150.

We arrived at the cancer clinic just south of Munich and while we waited for the doctor grupen fuhrer, Burton started chatting to a lady from New York who had been given months to live by her American oncologist and was now almost cancer-free. “You’ve got to film her,” Burton insisted. So I set up the PDX10 and a couple of radio mics and shot the two of them talking for 30 minutes. Afterwards I said, “We must do the reverse-angle questions.”

It was just Burton and me–no assistant. We couldn’t remember the questions he’d asked just minutes before. Burton did a few easy “How are you feeling?” questions to a no-longer-there subject and the usual noddies and smiles. I knew it wasn’t going to work.

The next day I decided to shoot with two cameras: one on the subject (who I’ll call “the victim”) and the other on Burton. The first shoot was in a small doctor’s room barely big enough for one camera–impossible with two.

At the next shoot I had a good background (BG) behind the victim, but the BG behind Burton was just awful. I only had enough light for one person, so Burton was lit by ambient and spill. That was it. I gave up. Concentrated on just shooting all the interviews with one camera. Shot 35 hours of interviews in 5 days. Not a tape left.

What I thought was going to be a 10-minute corporate project turned out to be a 2-hour DVD. Just as well that I packed all those old, used DV tapes.

The edit

Back from Germany and in San Francisco for the edit at my place, I needed Burton’s reverse-angle questions. Making corporate films and videos is not so much an artistic endeavor as it is a search for elegant solutions. The answer to this one was to shoot Burton asking questions against a greenscreen. I found backgrounds from the B-roll I shot in Germany. You need only a single frame for a BG.

Shooting greenscreen also gave me a chance to rewrite Burton’s questions, improving on his original, rambling live versions. I used a Lastolite greenscreen and Ultimatte AdvantEdge software in Final Cut Pro 5. Despite all the rubbish on Web forums about how you can’t get good keys from DV, the results were pretty good.

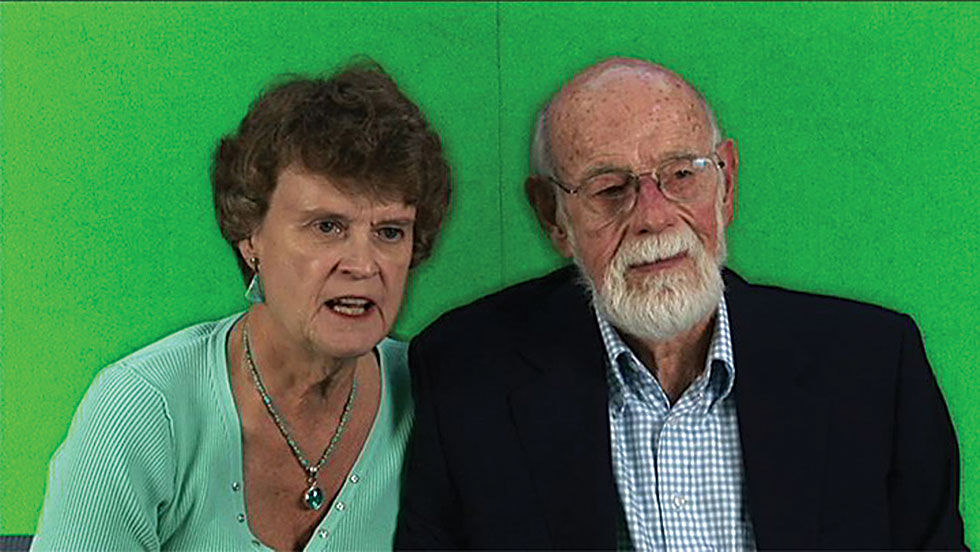

During 2005 I made a couple of other DVDs with Burton, including Curing Depression, and the technique of inserting his questions in post using greenscreen worked so well it became our standard practice. Burton was so pleased with greenscreen that he decided our next video, which was about stem cells, would be shot the same way for both the interviewees and later the reverse angles. It speeds up production if you can shoot anywhere. Just give me a room that’s 12-feet long. Camera to victim: 6 feet. Victim to greenscreen: 6 feet. I use backgrounds I’ve shot myself or pay a buck a photo to download from iStockphoto.com.

Tool kit

By 2006 I’d sold the PD150 and the PDX10 was lost, stolen, or strayed. To replace them, I bought two Sony HDV cameras: an HVR-Z1 and an A1. Don’t believe the “experts” who say the Z1U looks awful in 720 x 480 standard-def DV down-converted from 1080i. The widescreen DV images are much sharper than those of the PDX10, and PD150 footage looks very sad by comparison. So I shoot 1080i but edit in DV.

The irrepressible Burton has now decided to make a big movie for THE SILVER SCREEN. He talked to a Los Angeles-based feature film director who told him the HDV format wasn’t good enough for blowup to 35mm and that it was totally impossible to get a good chroma key for the big screen. Yet another expert in my life.

So I shot an HDV test of my daughter, Cissy, in front of the greenscreen and dropped in a background using Ultimatte AdvantEdge’s default settings. I did nothing except eye-dropper the green.

Burton had been told by an expert that it was impossible to get a key from HDV.

The next day my daughter Cissy was visiting us and I put up the green-screen on our deck and shot a quick test using only sunlight.

I removed the screen and shot our view, and then composited the two using Ultimatte AdvantEdge. Note: Although the shoot was HDV, the ultimate product was not HD, so Sargent edited in NTSC DV. All stills are from DV 4:1:1 timelines.

Other chroma-key software works, but try this with dvGarage’s dvMatte Pro, Primatte, or Keylight. There’s a lot of fiddling to be done before the key works in DV. The downside of AdvantEdge is its price of $1,500 versus dvMatte Pro’s $199, while Primatte and Keylight come free with Shake. At present, AdvantEdge won’t work at all in the new Intel-based Macs.

The feature film director is now history and we are making the BIG MOVIE 100-percent HDV greenscreen. Burton, who just turned 80 last month, likes to do the interviews on iChat from his home in Tiburon, CA. All my fault–I told Burton about documentary maker Errol Morris, who invented the Interrotron so his subjects looked directly at him and the lens. Burton took the idea and ran with it.

The victim sees and hears Burton via iChat. Burton sees and hears the victim. The victim looks straight at the lens. Burton stays at home. I fly to Canada.

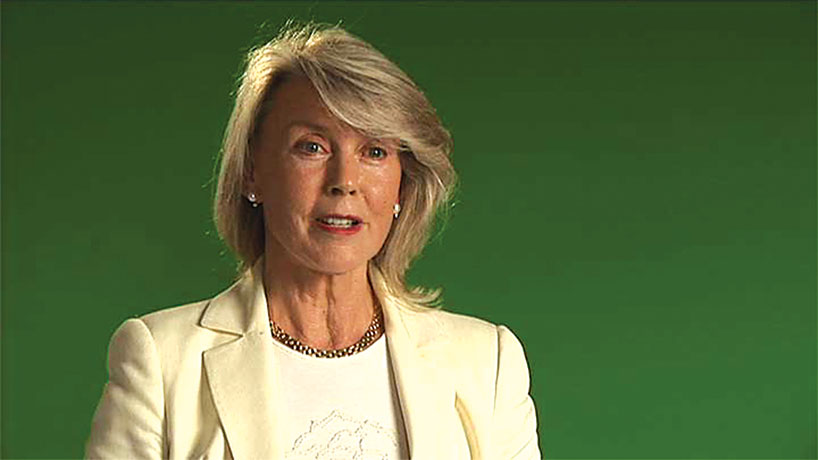

Burton Goldberg asking subjects questions. I tried to find a background for Burton that matched the location of the subject. All these shots of Burton were taken in my living room and were lit with a Rifa for key light and Dedo for back light.

Travel log

So here I am still stuck in the San Francisco airport waiting for my plane. Why don’t planes fly on time? I’ve been here 3 hours! I told you about my carry-on. Did I mention that if the checked luggage goes to Hawaii, I can still shoot from my carry-on? I’ve got carry-on cameras, mics, tapes, and batteries. Missing would be the lights and tripod, but I’ve made entire 1-hour TV documentaries without those. Phone directories on a table are a good camera support for an interview–use a table lamp for key light. It’s fast and easy.

The airline I’m taking restricts you to two items of checked luggage–each as heavy as 50 pounds. My greenscreen is one item. And that leaves me just one suitcase for everything else. I don’t like paying for valet parking if I can park across the road. Likewise, I don’t like paying for excess baggage. Many years ago I arrived at a rural airport in Italy. It was in the middle of nowhere, but another crew shooting Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World was waiting there. I was traveling light–just a few small camera bags, a tripod in a soft bag, and some personal luggage. The pros had lots of big metal flight cases. Guess who got on the small plane to Rome and who got left behind.

Tonight it’s just me traveling. I don’t want lots of big, heavy cases. That 50 pounds is a good limit for both the airline and me.

Over the years, I’ve bought every pro camera and lighting bag made, but they don’t work for one-man shooting. The beautifully made Petrol case for the Sony Z1 won’t fit in the overheads of the smaller jets. I know this for a fact, and you never want to part with your camera. I use a smaller camera bag and keep my babies close to me.

The $400 Petrol four-light case (they call it a bag!) weighs 30 pounds-that leaves just 20 pounds for the lights, light stands, tripods, monopod, dollies, and extension cords. Impossible.

So I use a lightweight Skyway 26-inch case–costs about $65 online and takes my 500-watt Rifa light, two dimmable 150-watt Dedos, two tripods, one monopod, three light stands, reflector, iChat speaker, Ethernet and power cables, and tonight I’ve packed wheels for the tripod. Plus a change of clothes, toothbrush, shaving cream, and so on. The secret is that it’s all packed tight. You don’t need all those fancy dividers. They just take up space. The Dedos have their own padded bag. All of this weighs 50 pounds exactly.

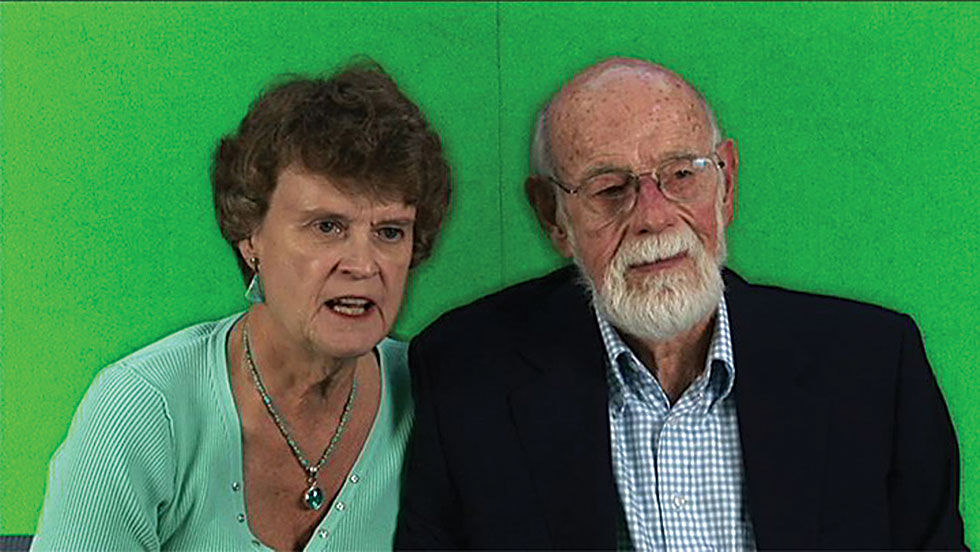

Tamisha and her son who was blind before receiving an umbilical stem cell injection in Tiajuana.

Tamisha's $1 iStockphoto.com background.

Time to board. Off to Canada. I’m starving but there’s no food–not even crackers. Crazy. This is a $650 ticket. I could fly to London and back for less. Why can’t they feed me? The airline needs profits. I need food.

October 2006, Edmonton. What is it about Canada? The first shoot I did here umpteen years ago, we arrived at midnight with a proper, expensive ATA Carnet. “What’s this?” asked the Canadian customs agent, who promptly put all our equipment into lockup for the night. The next day we had to pay a storage fee. One day of shooting down the drain. Welcome to Canada.

Location, location, location

So once again I arrive in Canada after midnight. “I’m here for one day, making a corporate video,” I tell the official.

“That door over there marked IMMIGRATION.”

“I don’t think you understand. I’m making a little video and will only be here for a day. Just one day,” I say.

“Tell the immigration officer over there.”

Fortunately IMMIGRATION was empty, apart from the two lady officials.

“Tell us about this video you’re shooting.”

“It’s for a video about hospital errors in the U.S.A.” (I thought that would please them.)

“Who do you work for?”

“Technically, I work for myself, but I have been commissioned by Burton Goldberg to do this shoot.”

“Do you have a camera?”

I show them the camera bag.

“Tell us about Burton Goldberg.”

Dear Reader, this is as close to verbatim as I can get. Eventually they let me go.

Catch a shuttle bus at 12:30 a.m. “Downtown Holiday Inn Express, please.” I arrived at the airport Holiday Inn Express 15 minutes later. “I said downtown.” “You said Holiday Inn.” “I said downtown!”

I arrive at the correct hotel at 2 a.m. Burton made the right decision to stay at home.

The next morning, I tour the location. I’m glad I brought my tripod wheels. Decide to do a tracking shot around the lab. They give me the boardroom to shoot the interview in. I put all the chairs into the corridor. Carry out most of the tables, too. Oh, the glamour of making videos. Put the MacBook on a table in front of the camera. Set the greenscreen against the far wall.

For the lights, I set up my Rifa 500-watt to the right of the camera. Put a Dedo at the rear wall for back light. Put a second Dedo down low near the victim’s chair facing the greenscreen. And turn off the house fluorescents.

Generally, I try to place my greenscreen 6 to 8 feet away from the subject. Ditto camera. It all depends on the room size. With smaller rooms, use the diagonal.

My formula for no-brainer lighting: Light-interviewer-camera, or interviewer-camera-light. The side of the face facing the camera goes darker than the other side. Generally, back light should be on the opposite side as the key light. Daylight back light with tungsten front light works well–just keep them on opposite sides.

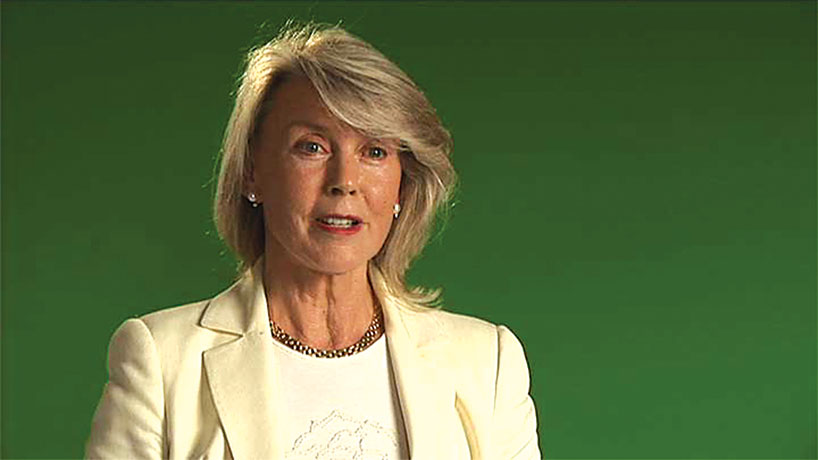

With good daylight coming into the room, say on the right, put the interviewer to the right of the camera. Turn the chair to get the best balance, but never have the daylight strike your subject straight on. Camera-interviewer-daylight from window. Add back light to suit. That’s why the dimmable Dedos work well. Just slide up the brightness. The shots of Katia shown were lit with daylight and a Dedo back light.

Katia lit by daylight and a 150-watt Dedo backlight. Greenscreen lit with daylight.

Katia composited against another iStockphoto.com background.

I continue preparing for the shot in the boardroom in Edmonton. Lights up. Camera ready. Lens at eye height. Chair in place for the victim. Here comes the hard part. I put the MacBook on phone directories until it’s just under the camera lens. Connect an Ethernet cable through the room’s Ethernet wall connector. Run the MacBook headphone out to a mini speaker on the table. The victim will be able to see and hear Burton via iChat. To do that, I set the camera input to DV in iChat’s preferences and set the microphone to line in.

This interview was shot against a Reflecmedia screen. I prefer a simple greenscreen. They're lighter to carry and don't suffer the seam seen here. I had to fix her green sweater in AdvantEdge. Her earrings were very close to the green-screen's color.

With an Internet connection up and running, this next bit is trickier. I shoot in 1080i HD but down-convert inside the camera to DV. Don’t use the Squeeze setting. Opt for Letter Box. I feed this via FireWire to the MacBook so Burton can see the victim. I use a double headphone adapter on the camera with one output feeding headphones and the second output connecting to the mic input on the MacBook.

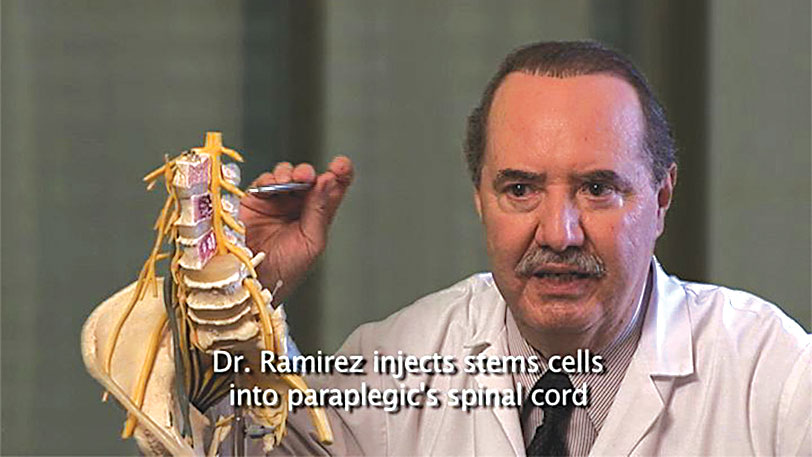

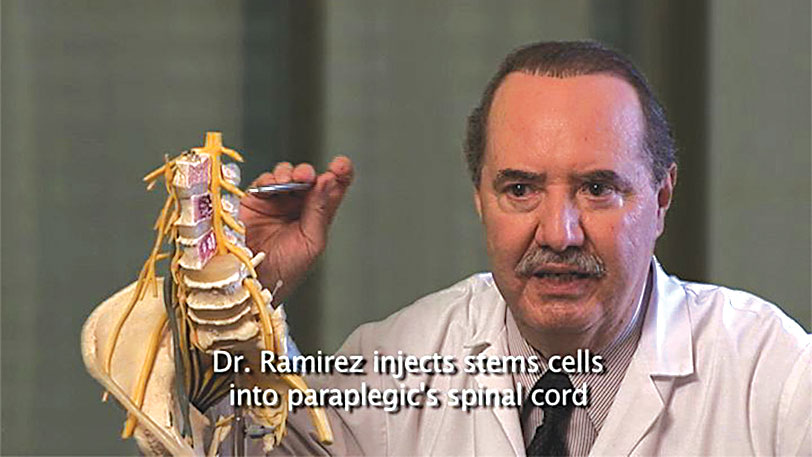

In Tijuana, Dr. Ramirez has had great results getting paraplegics to walk. However, the good doctor's real office is cluttered and not photogenic.

Dr. Ramierz shot against the background in the image above this one. The keylight is from my trusty Rifa 500, which fits nicely into my 26-inch Skyway suitcase. The back light is natural daylight.

Phone Burton 2,000 miles away. “Hi Burton. Time to log on to iChat. Just accept my invitation for a video chat. Great to see you. Is that Belinda in the kitchen?”

“We’ve got a good connection but his face looks a bit dark to me.”

“No Burton, it’s just your monitor.”

“I can’t see one side of his face. It’s dark.”

“Must be the iChat connection adding contrast. Looks good here. Ready when you are.”

“Hi, I’m Burton. Thank you for doing this interview. Remember, when you answer my questions, look into the lens. Keep your eyes there. Don’t look at me. You’re on a big silver screen. Are you running, Stefan?”

“Yes Burton. I’m running. Start whenever you like.”