I’ve landed the job, shot it, edited it. Now it’s time for the big client screening. Watch them watching. When the lights come up, will it be?

“Oh my God! It’s freaking awesome! Capital-A amazing! You rock!”

OR…

“It’s good.” He said the G word; polite speak for it sucks. He hated it.

“No, I thought was good. I really liked it. It was, well… good.”

PREMATURE REJECTION. LONDON, U.K. 1972. I’d made some conference films for Black & Decker. They recommend me to Ron Hickman as they have licensed from him an invention called the Workmate. A demo film is needed, and Ron is coming to London to meet and see some of my work.

We’re in a screening room in Soho. I’ve put together a reel of three recent productions: The Redifon AWACS Flight Simulator, a film I made for Margaret Thatcher on education in England and my own favorite, The Birdseye Pea Story.

The lights dim. For the next 20 minutes, I sit back, proudly watching my three babies. The lights come up. I’m pumped, ready for praise.

But Hickman is hopping mad. “Are you stupid or something? I want a demonstration film showing a unique workbench and you give me school children, high-tech simulators and, worst of all, a film about harvesting peas. Have you ever made a construction film? Houses going up, do-it-yourself gadgets, carpentry demonstrations… ?!”

With that, Hickman leaves.

He’s gone. I blew it.

CREWS FOR CRUISE. MALAGA, SPAIN, 1994. It’s the start of a five-day Mediterranean cruise. Our client, John Kenning, has written a series of books on how to get glam jobs — i.e. how to become a model, an airline steward or work on a cruise ship.

Tricia and I are in port aboard the Fred Olsen cruise ship Black Prince. It looks like fun, but, knowing SARGENT’S LAW, we’re careful that we don’t enjoy ourselves too much.

John has a lively personality. I make him the linkman. Put him on camera. Shoot an opener, a closing and some bridges: “Start cruising, it’s a job and a holiday all in one!”

John flies back to London. We sail off to the Greek Isles.

For the next five days, I don’t stop shooting. I’m up at daybreak, shoot all day. Every time we arrive at a Mediterranean isle, I’m down the gangplank first. It’s hot, the Betacam is heavy and I’m walking backwards interviewing the ship’s tour guide.

I shoot long takes so I don’t miss the unexpected, such as the crew member who accidentally falls in the pool while dodging a drink-carrying waiter.

Back in London. John sees the edit. The lights come up. Now the payoff.

“You’ve got a lot of lucky shots.”

“The guy falling into the pool?”

“No, it’s all lucky shots.”

I hear this all the time. Only last week: the lights come up and the client says my shots are “lucky.” Is it just me, or do real cameramen hear this too?

Francis: “Nice work, Vittorio — you got some lucky shots.”

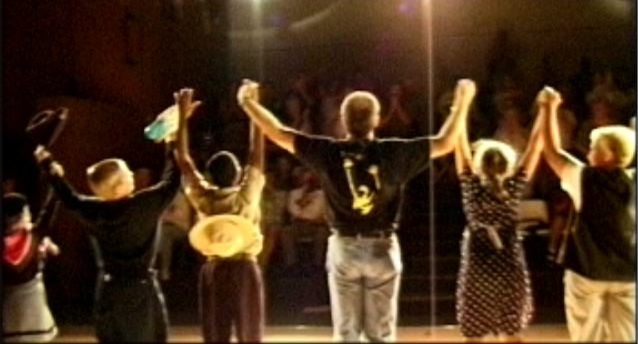

TEARS FOR CHEERS. SAN RAFAEL, CALIFORNIA. 1999. I’m making a pro bono for Peter Meyers, who teaches kids how to act at his Vector Theater Conservatory.

I use a cinéma vérité style of shooting; wiring up Peter and his teachers with radio mikes. Sit in for a few days with my PD150. I’m invisible; a neat trick.

I run the edit to Peter. He has no idea what I’ve shot (I was invisible). He’s watching intently, smiling… now his expression changes. A tear rolls down his cheek. He’s crying. The lights come up — he’s a mess. I’ve made hundreds of films but no one has ever cried before. What did I do wrong?

“It’s so beautiful. You’ve captured all my dreams, hopes and aspirations.”

“Come on, Peter. It’s good, but not that good.”

Now I’ve used the G word.