CENTRAL QUEENSLAND, AUSTRALIA. February 1968. I’m in a phone booth at sunset in a government farm and training facility for native aborigines. I get through to Dick Mason, my producer at Film Australia in Sydney, 1,000 miles south.

“Dick, this is a disaster. It’s a concentration camp for aborigines. I thought I was meant to be making a film called The Aboriginal in Industry.”

“Calm down.”

“And there’s a curfew. They can’t go out. The local townsfolk don’t want them. The aborigines’ windows have no glass. I interviewed the Little Hitler in charge and he said on camera, ‘You can’t trust an aboriginal with glass!’”

Dick catches a plane and drives for four hours. Discovers everything I have said is true. The shoot is aborted and we evacuate.

Plan B: Go to Darwin, find other “aboriginals in industry.” So, this is how documentaries are made.

DARWIN, NORTHERN TERRITORY. Three days of scouring Darwin and my PA has found an aborigine street cleaner and an aborigine garbage collector. I phone Dick in Sydney to tell him the bad news.

“Stay where you are. We’re working on it.”

For some time I’ve been wondering why, with so many directors on staff, they hired an outsider, lucky me. Now I know. This job is doomed.

The next day, Dick phones back. There’s an island between Australia and New Guinea where the local missionary did a deal that forces the BHP mining company to employ aborigines.

Plan C: Go there. And you thought we know what we’re doing.

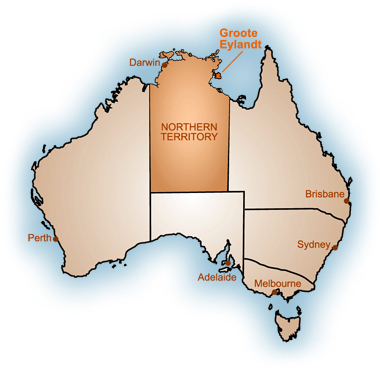

We fly to Groote Eylandt, Gulf of Carpentaria. Land in the middle of the jungle. Wait three hours for the search party.

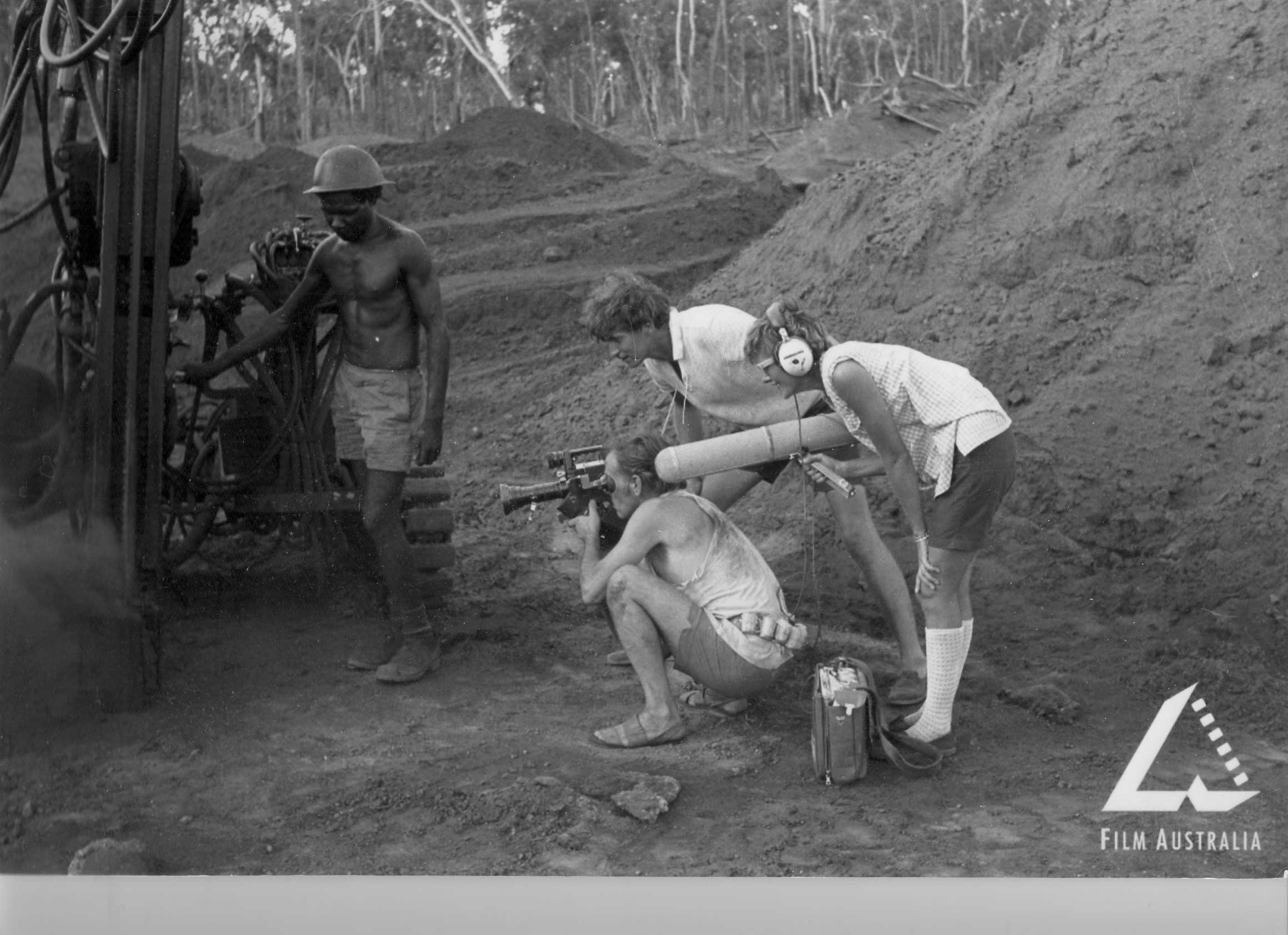

An aboriginal miner is drilling a hole for blasting. I’m “directing,” Keith is shooting and Rosemary is recording the sound.

GROOTE EYLANDT.

I meet the missionary. Years earlier, a government surveyor had confided to him that the island was rich in manganese. He flew to Darwin and secured the mining rights for the aboriginals and laid down terms: They must be hired one-for-one with “white” Australians and paid the same wage.

The aborigines’ sanctuary is now a mine. Their reward is houses, schools, microwaves and motorcycles. This is going to be a tough. The film is being paid for by the Australian government. Make something critical; it will be junked. Go the other way — it’s a cop-out.

My solution is ART. Trick my government client into thinking this isn’t a run-of-the-mill documentary but something way more special: An artistic masterpiece.

I DID IT MY WAY. Difficult balance. Too arty and you lose the audience and message. Too conventional and the suits will climb all over it.

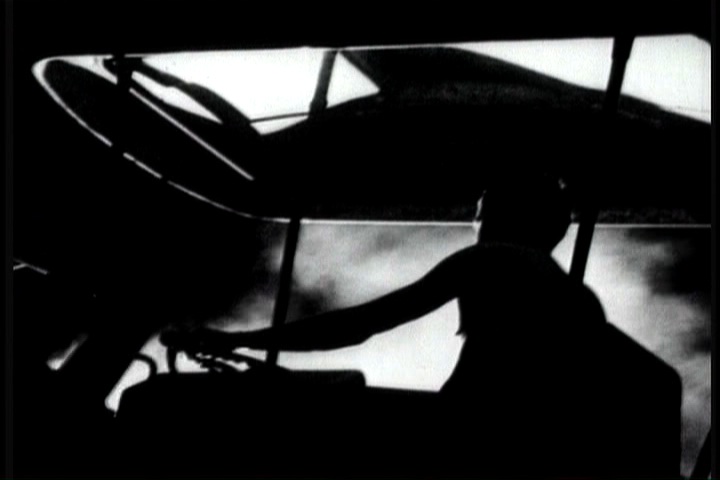

So: Contrived compositions, often with the background or foreground way out of focus. Shooting through something always works… rain, smoke, fire, dust, heat haze, magnesium flares.

Combinations are fantastic — out-of-focus plus fire, smoke and heat haze all together! Wow! No talking heads, no name captions, just unidentified voiceovers. Heard but unseen distant explosions.

I dread showing my rough cut to Dick, but when I do he’s ecstatic: “I love it, go over the top.” Try and stop me.

SUITS IN SHOCK. Sydney. We show it to the government men. The lights come up. Silence. Dick looks at them. More stunned silence.

“Unusual,” says one. “Very powerful,” says Dick. “Narrator?” asks a suit.

Dick turns to them, “I didn’t want to say this in front of Stefan, but it’s an artistic triumph. A tour-de-force. To change it would be like re-touching Picasso’s Guernica.”

That’s what a producer does. He sells your meager offering to the client.

It’s approved, as-is.

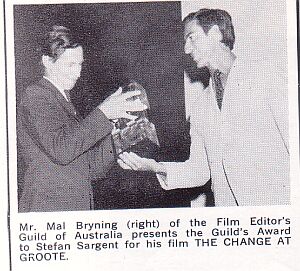

The project later wins top awards for direction, photography, editing

and — wait for it — Best Australian Film of The Year.

For me, it was just a means to an end, to get it approved, no changes.

See it here